As you know, we like to get our hands dirty with nature play at our child care centres. Our children are allowed to experience good old-fashioned childhood fun, playing in the dirt, mud and outdoors in general. Our Bush Kindy Explorers program is a great example of this where the children are exposed to nature and all its wonders including the micro-bugs that live in the dirt, plants and water. They also love tending the herb and veggie gardens at the centres where they get to dig in the dirt and nurture the seedlings into full grown edible plants.

So what exactly is the Hygiene Hypothesis apart from being a mouthful? Well, it’s the concept of exposing people to germs in early childhood to build immunity. Including nature play at our centre is a great way for us to do this.

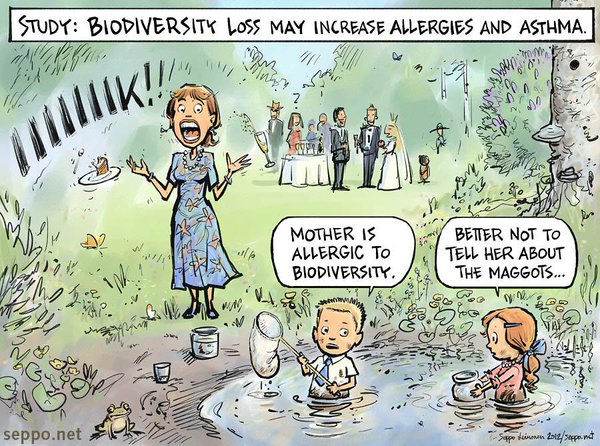

For many years scientists have suggested that the Hygiene Hypothesis explains the global increase of allergic and autoimmune diseases in urban settings and in 2012 Medical professionals at Brigham and Women’s Hospital were able to prove this theory with biologic support.

Previous human studies have suggested that early life exposure to microbes (i.e., germs) is an important determinant of adulthood sensitivity to allergic and autoimmune diseases such as hay fever, asthma and inflammatory bowel disease, but it wasn’t proven until 2012.

Researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) have conducted a study that provides evidence supporting the hygiene hypothesis, as well as a potential mechanism by which it might occur.

The researchers studied the immune system of mice lacking bacteria or any other microbes (“germ-free mice”) and compared them to mice living in a normal environment with microbes. They found that germ-free mice had exaggerated inflammation of the lungs and colon resembling asthma and colitis, respectively. This was caused by the hyperactivity of a unique class of T cells (immune cells) that had been previously linked to these disorders in both mice and humans.

Most importantly, the researchers discovered that exposing the germ-free mice to microbes during their first weeks of life, but not when exposed later in adult life, led to a normalized immune system and prevention of diseases. Moreover, the protection provided by early-life exposure to microbes was long-lasting, as predicted by the hygiene hypothesis.

“These studies show the critical importance of proper immune conditioning by microbes during the earliest periods of life,” said Richard Blumberg, MD, chief for the BWH Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endoscopy, and co-senior study author, in collaboration with Dennis Kasper, MD, director of BWH’s Channing Laboratory and co-senior study author.

“Also now knowing a potential mechanism will allow scientists to potentially identify the microbial factors important in determining protection from allergic and autoimmune diseases later in life.”

In light of the findings, the researchers caution that further research is still needed in humans.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Crohns Colitis Foundation of America, Harvard Digestive Diseases Center, Medizinausschuss Schleswig-Holstein, and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.